How Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island transformed the pirate from bloodthirsty villain to morally complex guide for young readers

Children’s literature has character archetypes, ranging from mythical beasts to knights, kings, and everything. Among these figures, the pirate began to emerge as a prominent character in the 19th century, specifically in Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Treasure Island. Prior to his novel, pirates filled the role of the villain and were typically depicted as bloodthirsty, self-serving, and greedy characters. However, over time, the role of the pirate has transformed from the aforementioned villain to a more complex character, filling the role of the villain and a hero-like figure, depending on the narrative.

This raises the question: how did the pirate transform from a primarily villainous figure into a morally ambiguous character in literature, especially in children’s stories where themes of violence and greed might seem out of place? Is it the allure of their unbridled freedom, the thrill of treasure hunting, or the rebellious spirit they embody? The answer lies in all of these factors. Pirates in children’s literature, especially in Treasure Island, offer a nuanced moral framework that mirrors the complex dilemmas children face as they grow. By presenting pirates as morally ambiguous figures, these stories create a space for young people to navigate real-world ethical challenges. This paper will examine the evolving role of the pirate in children’s literature, focusing on Treasure Island. It will explore how the role of the pirate evolved from a cautionary villain into a complex character and how these morally ambiguous characters arose.

The Story That Changed Everything

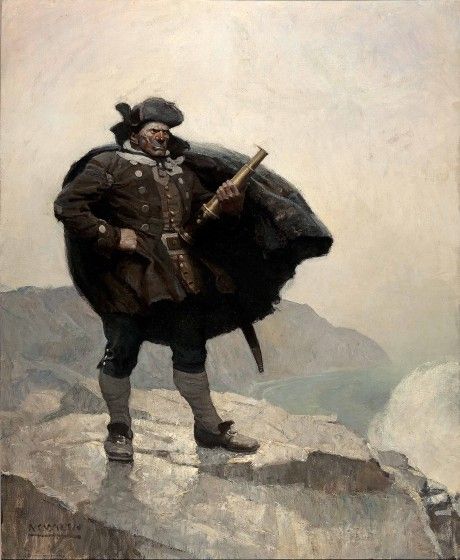

Treasure Island by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, released in 1883, follows the story of a young boy, Jim Hawkins, living in an unnamed town in the United Kingdom and working at his family’s tavern, the Admiral Benbow Inn. The story begins with Jim’s discovery of a treasure map from a deceased pirate who stayed at his family’s inn; this discovery leads Jim to be joined by characters such as Dr. Livesey, the town doctor and magistrate, Captain Smollett, the captain of the Hispaniola, the ship in which they are using to navigate to where the treasure is, and Long John Silver, a pirate disguised as the crew’s cook who later conspires a mutiny on the ship in order to obtain the treasure himself. As the voyage unfolds, Jim must navigate betrayal, danger, and complex moral dilemmas as mutiny ensues. Treasure Island captures both the childlike nature of adventure and treasure hunting while simultaneously capturing mature realities of greed, violence, and decision-making, with the figure of the pirate embodying these themes. This novel established many of the tropes and caricatures of the pirate we see today, establishing the pirate from a stereotypical villain to a more complex set of characteristics and morals that we understand today.

The Historical Context

The late 19th century, during the time of the publication of Treasure Island, was marked by a period of exponential growth in the United Kingdom and America, encapsulated by industrial and economic growth and cultural shifts within society. As Ward highlights in his essay, “The Pleasure of Your Heart’: ‘Treasure Island’ and the Appeal of Boys’ Adventure Fiction,” among this rapid growth of Empire also emerged the need for a societal narrative of growth and change, which was captured among children’s literature as Ward outlines the need for children to be able to understand complex societal problems, as well as adult readers who wish to maintain a childlike nature and thought process which could be contained in the “boy’s adventure genre” stating, “Treasure Island on, the central purpose of Stevenson the writer was to redress the situation, to represent an increasingly complex body of romantic fiction, which would be ‘to a grown man what play is to the child.’” (Ward 306) Stevenson wished to capture both the adult perspective of the childlike nature and perspective of the world while simultaneously appealing to both adults and children alike. Stevenson did this through Treasure Island by offering complex problems of the adult world through a child’s perspective of Jim Hawkins, thus appealing to both adults and cementing Treasure Island as a pivotal piece of children’s literature.

The Child’s Perspective as Moral Compass

This concept of Jim navigating adult problems with a childlike perspective can be viewed in scenes throughout the novel, such as that where Dr. Livesey suggests Jim’s perspective is more valuable than the adults as it is not clouded by adult corruption, stating, “Jim here… can help us more than anyone. The men are not shy with him, and Jim is a noticing lad,” (Stevenson 101) highlighting Jim’s exceptional ability to notice and understand crucial details despite his age and his trustworthiness as the characters perceive him to be more innocent than the adults of the novel. Furthermore, Ward alludes to characters such as Billy Bones and Long John Silver being trusting of Jim due to his childlike perspective as he states, “Although giving an account of the adventure is an adult responsibility, Jim gains the experience to do so as a result, not of his acquired knowledge, but of his boyish innocence, which makes even Billy Bones, Ben Gunn, and Long John Silver trust him without the long acquaintance that accounts more readily for the trust of the doctor and the squire.” (Ward 308) Highlighting the role of the child’s perspective in children’s literature and furthering the claim of Treasure Island providing a source of children’s literature where complex moral and physical situations are provided to the reader and protagonist alike and how to operate within that framework from a child’s perspective. This concept even goes as far as the drafting of the story as Stevenson’s thirteen-year-old stepson helped conceive many parts of the story, such as that of the treasure map, highlighting the synthesis of the child perspective via Stevenson’s stepson and processed through an adult perspective via Stevenson.

The Framework of Amoral Fiction

The theory of conflicting or complex moral characters and personas in children’s literature has been discussed in Clawson’s essay “Treasure Island and The Chocolate War: Fostering Morally Mature Young Adults through Amoral Fiction,” where Clawson defines this framework as amoral fiction, defining it as “Fiction that presents characters or situations that cannot be classified as either good or bad. Amoral fiction allows readers to navigate murky moral situations without the help or heavy handedness of adult preaching.” (Clawson 54) This amoral fiction can be embodied in characters such as Long John Silver, who is a pirate yet is not portrayed in the way one might imagine. Instead, he is charismatic, clever, intelligent, and beautiful to a degree and amicable to those who threatened him, shifting the reader’s perspective from villain to a more anti-hero role. This portrayal of Long John Silver as he navigates between betrayal and loyalty speaks to a larger image of the trope of the pirate as a one-dimensional villain but rather a complex archetype that offers a perspective that mirrors that of the natural world of complex moral frameworks and perspectives. Silver’s somewhat parental role of Jim throughout the novel offers a unique perspective of the pirate as a self-centered individual and a unique perspective of human nature beyond the one-dimensional pirate trope and humanizing the pirate. The humanization of a traditional villain role offers a complex situation for the protagonist and reader alike, thus drawing on Clawson’s claim that Treasure Island is a pivotal novel in children’s literature as it portrays “amoral fiction.”

Navigating Moral Complexity

This concept of moral ambiguity can be seen further in Jim’s interactions and relationships with characters throughout the novel who would require complex moral compasses to navigate, such as Jim’s relationship with Long John Silver. Jim’s relationship with Silver was both tenuous and amicable at times, presenting Jim with conflicting moral lessons, thus challenging Jim’s youthful innocence and shaping his sense of morality, fitting into the role of children’s literature as a lesson-giving piece of work. Initially, Silver protected Jim from the mutineers, challenging Jim’s view of Silver as an archetypal villain and presenting Jim with the opportunity to evaluate actions beyond surface-level appearances, fostering a deeper understanding of human complexity.

This growth and understanding of human complexity can be seen in his interaction with Ben Gunn, a marooned pirate driven to insanity due to his isolation on the island. This insanity leads Ben Gunn to present himself as eccentric, which could be off-putting and lead people to distrust him. However, Jim can navigate people’s intentions rather than relying on adult figures like Dr. Livesey and Silver, trusting Ben Gunn, who plays a pivotal role in Jim and his crewmate’s safe escape and finding of treasure. Furthermore, Jim’s confrontation with Silver after being captured showcases his moral fortitude. When Jim asserts, “I no more fear you than I fear a fly,” (Stevenson 232) he not only takes a stand against Silver’s manipulation but also exhibits his blossoming confidence in his moral convictions.

Pirates as Symbols of Childhood Development

Shifting the focus to childhood development and the role the pirates fill in children’s narratives, the pirate archetype serves as an archetype of Jim’s childhood development and, on a macro level, as an archetype of childhood growth. Pirates such as Silver, with his charisma, cunning, and benevolent nature, challenge the notion of traditional good and evil and provide a framework for young people to navigate growth in reality.

The pirate figure, emblematic of rebellion and pushback against societal norms, challenges young readers to think critically and navigate tenuous decisions. This struggle against authority and adulthood can be seen in Jim’s struggle with Dr. Livesey, who, as Valint discusses in the article “The Child’s Resistance to Adulthood in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island: Refusing to Parrot,” represents the cold and calculated aspects of adulthood as throughout the novel Dr. Livesey can keep a calm and collected demeanor in the face of adversity such as that with his interaction in the beginning parts of the novel where Dr. Livesey confronts Billy Bones, a hardened pirate who has taken refuge at Jim’s family tavern causing discern and unease among the people. “I’m not a doctor only; I’m a magistrate; and if I catch a breath of complaint against you, if it’s only for a piece of incivility like tonight’s, I’ll take effectual means to have you hunted down and routed out of this. Let that suffice.” (Stevenson 9) This interaction, as Valint would suggest, gives a perspective of both adulthood and the role of the doctor figure in the 19th century. Unlike the pirate, the doctor figure is always level-headed and does things by the book, following logic rather than one’s heart. In contrast to characters such as Billy Bones, who can be irrational at times and bombastic in nature, opting to drink alcohol still even though the doctor warned him it would be the end of him. Shows the stark contrast between the doctor and the pirate figure in Treasure Island.

The Struggle Between Order and Freedom

This struggle of the doctor and pirate figure, as Valint outlines, suggests a broader theme in the novel, of doctor figures in the 19th century representing aspects of adulthood such as the separation of emotion from decision-making and following logic and rules. This is opposed to the pirate figure, which can represent aspects of childhood, such as acting with one’s heart and not acting logically. Thus, throughout the novel, Jim challenges Dr. Livesey’s authority, such as in the scene where Jim openly defies Livesey’s order to remain on the ship when boarding land. This rejection of authority leads to Jim’s introduction to Ben Gunn, who, as earlier stated, is a pivotal character in the novel and helps provide safe passage for Jim and his crewmates.

This struggle of authority in Jim’s narrative between the pirate figure and the doctor illustrates a broader theme of growing and the struggle of growing up and finding an equilibrium between maintaining one’s childlike innocence and nature while simultaneously having to fit into society’s rigid rules and structures. Jim’s rejection of the doctor furthermore can be seen as a rejection of the cold rigidness of adulthood, as Valint states: “Jim will not be the parrot who acquiesces to such a desire, because being an adult means being cold, emotionless, and greedy.” (Valint) As Valint argues, Livesey is not the adult figure in the novel who represents good; instead, he is a figure that represents the rigid structure and rules adulthood contains, and thus, the pirate figure is the rejection of those rules and structures, acting somewhat as a bridge between the adult world and childlike nature. Furthermore, this is represented in Livesey as a magistrate, which one could argue is the epitome of the adult world and rule-following. This complex nature of piracy, representing childlike nature while also simultaneously representing adult danger, shows the complexity of the moral framework of the pirate and the appeal it could have towards children.

The Playspace of Moral Development

The childhood development aspect of the novel and the role of the pirate regarding childhood development can be viewed in Bushell’s work “Negative and Positive PlaySpace in Treasure Island,” which discusses the role of a “Positive playspace” regarding childhood development in fostering space for children where they can explore and test boundaries safely, and a “negative playspace” would be the inverse. The novel setting, Bushell argues, represents both a positive playspace as Jim is not bound to strict societal rules on the ship or the island. However, it also fills the role of negative playspace as Jim is under constant threat of bodily harm from both the pirates and nature, as seen with Jim’s encounter with a snake when arriving on the island. This is further extrapolated as Jim is bound to two authority figures in the novel, the pirate and the doctor, both of which are bound to complex moral frameworks, which one could argue are the inverse of each other. As earlier stated, the doctor represents the rigid rules and structures of society and adulthood but provides safety and order. At the same time, the pirate embodies a more free, childlike nature but lacks order, which in turn provides an opportunity for immense danger. However, one could argue that the “negative” playspace for Jim reflects the real world, as, in reality, there is no space where one is devoid of danger and harm. Jim has to decide which framework he must operate under within this space. However, Jim rejects both while taking in aspects of each, such as relying on the rule of law when captured by Long John Silver, representing the lessons taught by Dr. Livesey, while also taking in aspects of the pirate, such as boarding the Hispaniola and challenging the men on the ship. The aspect of Jim taking on parts of the pirate can be interpreted as Jim’s growth to differentiate good aspects of an individual, even that of a pirate who was viewed as an archetypal villain prior to this novel.

Ultimately, this overlap of the pirate narrative serves as a microcosm of childhood play spaces, which can be seen in other works post Treasure Island, such as that of the narrative of Peter Pan, where the story takes place completely in children’s “playspace.” Within this playspace, Treasure Island mirrors the real world and emphasizes the complexities of reality as one of guidance and self-discovery. The pirate figure is a guideline for this self-discovery by portraying a complex moral framework Jim must figure out on his own while learning from these authoritative figures, such as Silver. Thus, it sheds light on the pirate figure as not one of outright evil but a complex character from which children can learn and take aspects, such as freedom, while being able to conceptualize negative aspects of the pirate, such as violence and brutishness.

The Lasting Impact on Children’s Literature

Shifting focus back to Ward’s analysis of Treasure Island and the lasting impact it had within the theme of “boy’s adventure” in his work “‘THE PLEASURE OF YOUR HEART’: ‘TREASURE ISLAND’ AND THE APPEAL OF BOYS’ ADVENTURE FICTION,” Ward discusses the long and lasting impact of Treasure Island on how the theme of boyhood is perceived and constructed within the novel, and further works post Treasure Island and arguing that Treasure Island appeals to universal tropes within children’s literature, such as adventure, exploration, and danger. Within that framework of children’s literature, the figure of the pirate weaves perfectly, intertwining the thrill of exploration and adventure while producing danger and excitement, acting as a bridge between childhood fantasy and mature adult themes. As Ward states, “Stevenson makes us realize that its peculiar appeal to both juvenile and adult readers is, in part, the result of the interplay of boyish and mature sensibilities that produced it.” (Ward 306) This interplay of “boyish and mature sensibilities” is enacted via the pirate figure, which, as discussed earlier, represents aspects of both childlike and adult sensibilities. This representation of the pirate can be viewed conceptualized as a broader theme of the 19th century as people longed for this concept of adventure and freedom being weighed down by the Empire in which the pirate figure can be used as a vehicle in fiction and children’s literature to express this longing for freedom, however irrational it may be. The pirate itself can be viewed as an irrational figure rejecting society to achieve their ambitions and goals. Thus, Treasure Island offers a glimpse into a more human-like pirate figure made of complex goals and desires rather than being an evil figure. Transitioning the pirate from an evil force to a more human force and human nature is a complex framework of good and evil that the pirate can fill.

The Pirate as Guide to Self-Discovery

The pirate archetype within Treasure Island plays a crucial role in self-development and self-discovery as it offers a window into the complex moral framework of society and human nature, acting as a rebellious force while acting in its own self-interest. This conflicting nature of the pirate offers an opportunity, specifically in children’s literature, for young readers to explore their moral framework and be able to ascertain and develop their judgment skills as Jim does throughout the novel, shifting trust and focus between Silver and Livesey taking in positive aspects of both characters while rejecting the negative ones. This ability gained from reading the novel speaks to the broader theme of children’s literature as both a guiding piece of literature and offering entertainment and excitement in the form of adventure and danger, which the pirate perfectly fills. The dual nature of piracy makes them a compelling force within children’s literature, presenting rebellion as both a risk and a reward, regarding Silver’s rebellion being quelled. Yet, Jim’s rebellion to authority is rewarded. They encourage young readers to defy authority but in a meaningful manner rather than the self-serving manner of Silver. However, Silver is not entirely punished for his rebellion due to his acts of morality, thus presenting the reader with both a reward for showing humanity and a portrayal of the pirate as more of an anti-hero rather than a villain. Thus cementing the pirate figure in children’s literature as a guiding figure in the complexities of the real world.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Treasure Island presents the alluring nature of the pirate figure as one of the extreme dualities, from compassion to bloodshed to rebellion and self-interest, encapsulating the complex moral conundrums of reality and removing the binary of good and evil, presenting characters such as Long John Silver as complex characters filled with contradiction yet shows acts of humility and compassion while simultaneously being violent and cruel. This shows the conflicting nature between boyhood and adulthood and the steps one must take to form one’s degree of autonomy while still being kind-hearted, as Jim does. Throughout Jim’s interactions with both adult figures of Livesey and Silver, Jim is challenged with complicated moral decisions drawing on both depending on the scenario; this ability to draw on both the pirate and the doctor shows Jim’s growth as a character while also pertaining his childlike nature and need for guidance. The legacy of Treasure Island and the shift in the portrayal of the pirate as an antiquated villain to a more anti-hero role can not be understated, with media such as Pirates of the Caribbean portraying this concept as one of the key figures of the series is that of Jack Sparrow, a pirate who arguably shares many of the same complexities of that of Silver, acting on his self-interest, yet showing signs of humility and compassion. Thus reflecting the long-lasting impact of Treasure Island and the literary shift of the pirate narrative in children’s media.

References

Bushell, Sally. “Negative and Positive Play Space in Treasure Island.” Barnelitterært forskningstidsskrift, vol. 13, no. 1, 17 Aug. 2022, pp. 1-10.

Clawson, Nicole P. “Treasure Island and The Chocolate War: Fostering Morally Mature Young Adults through Amoral Fiction.”

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Treasure Island. London, Cassell and Company, 1883.

Valint, Alexandra. “The Child’s Resistance to Adulthood in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island: Refusing to Parrot.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 58, no. 1, 2015, pp. 3-29.

Ward, Hayden W. “‘The Pleasure of Your Heart’: Treasure Island and the Appeal of Boys’ Adventure Fiction.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 6, no. 3, 1974, pp. 304–17.

Leave a comment